Museums are not about rare and fabulous objects safely locked behind protective glass. At least the good ones aren’t.

Museums should be about people and the lives they lived.

Museums should tell stories.

And never have I found more stories in a single place than at the fabulous Museum of Appalachia in Tennessee.

The place is full of stories. The place is a story itself.

In 1967, John Rice Irwin, a cultural historian – began collecting stuff –old stuff. And with that stuff, he collected stories of his native Tennessee. He wrote those stories down – so they would never be forgotten…

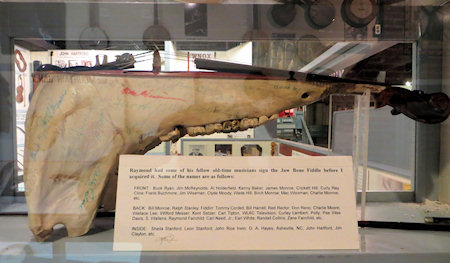

Here’s one of them – the story of Raymond Fairchild’s Jawbone Fiddle – in his own words.

“Old Man Willis Harris gave me that mule when I was about seven years old and I named him Siron Slick.

I plowed him to raise our crops and rode him. He made a living for us. Him and an old cow.

One day old Siron just up and died. A lot of people don’t understand how you can get so close to an old mule like that.

We buried him and I guess it was several years before I went back and I found that varmints and dogs had dug up Siron’s bones. I saw his old skull lying there and it made me kinda sad and I took it home.

I was talking to a friend of mine about old Siron Slick… and he said if you thought that much of him, bring that old jawbone over and I’ll make something out of it for you.

I run into him a year or so later and he said I’ve got your jawbone fixed.

He’d built a pretty fiddle sort of inside old Siron’s jawbones. And I swear it’s not a bad sounding fiddle. He liked it so much that he wouldn’t let me have it. Said I’d have to wait ‘til after he died. Well, he kept it till he died and not long after his wife called me and told me to come and get my fiddle.”

Raymond later donated that fiddle to John Rice Irwin and the museum he founded.

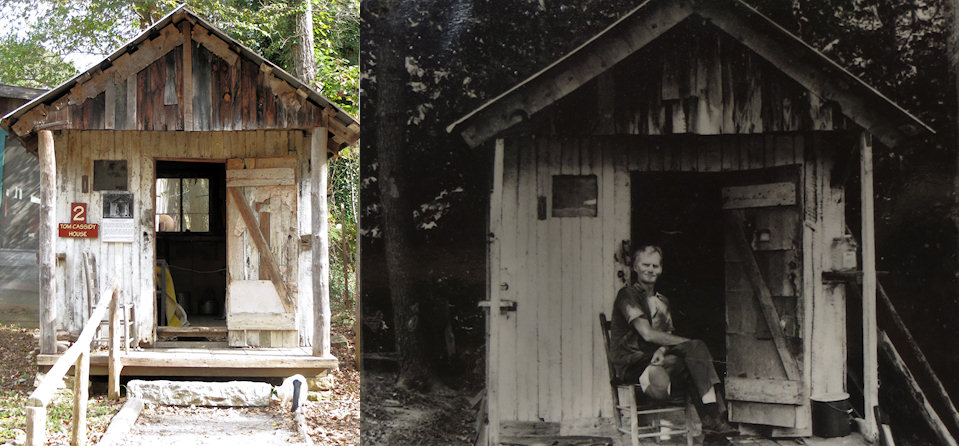

The Museum of Appalachia is a collection of buildings and stuff – that tells the story of life in the Appalachian mountains and of the people who lived there. It’s a walk through the past.

Sometime that past isn’t as far back as one might think – Tom Cassidy lived in this cabin lined with cardboard to keep out the cold until his death in 1989. That’s not so long ago.

Irwin hand wrote labels for the objects he collected – and those labels tell their stories..

A cradle where Louise Stooksbury (born 1858) rocked her fifteen children.

A toy wooden wagon owned Elsie Joe Henderson – the daughter of a judge – made for her by the family’s black caretaker, old Jack Tate.

George Burkhart and his wife Sapphira, who made their home in the hollow truck on a tree and raised six children there – including three sons who were all good blacksmiths.

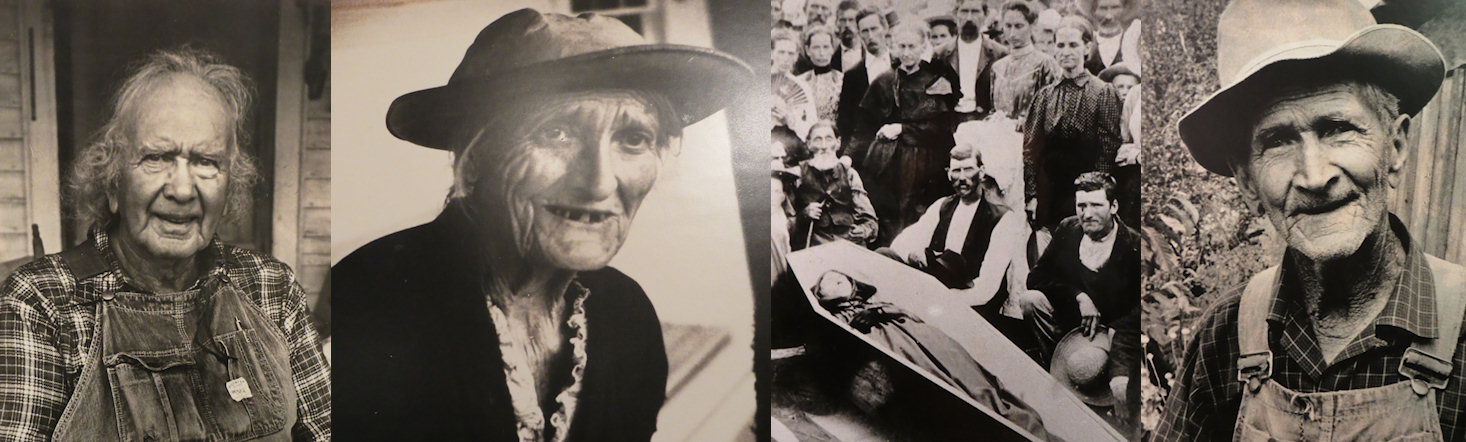

Some of the stories were straight from the horse’s mouth as it were – told by older people who remembered. Others were passed on by children or grandchildren… but they are the true folk history of Appalachia and it’s people.

People like Dr Andrew Jackson Osborne, who was born in 1869.

People would walk for miles to visit his medicine house and he would also travel on horseback to see patients long distances away. It was said he often slept on that horse’s back. When he reached the medicine house, the horse would nudge the door to make enough noise to wake the doc.

He never charged his patients – but those who could pay something, did.

He was particularly distressed by the infant mortality rates in the mountains – and tragically ten of his own children died at birth or in early infancy.

Doc Osborne ministered to the people all his life and was poor all his life. When he died in April 1937 the Rev Frank Phipps had to find a suit for him to be buried in.

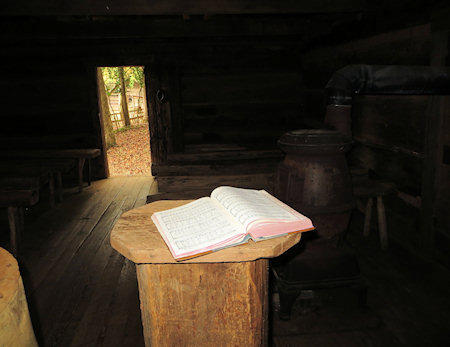

Tucked away in a corner of the main museum building, I found The Murder Bench from War Creek church. What a story it had to tell.

Apparently a feud started when a wandering hog destroyed the mash at a neighbours whiskey still. That feud claimed several lives. One of the victims was ambushed outside a church. Mortally wounded, he was carried inside to die on this bench. Even after the dispute was ended, the stain left by his blood on the end of the bench was too great a reminder of the bloody feud – and churchgoers tried to burn it away. But that only left a burn mark as an equally strong reminder of old animosities.

That’s what this museum is all about – it’s a story of the people. Many of these people never had a job as we understand it. They grew corn and raised pigs to feed their families. Women wove fabric for clothes. People built their own homes. And communities shared the results of their labours.

But perhaps the most amazing story of all is that all this arises from one man’s love of his people and his history. Thank you John Rice Irwin – you have given us a treasure equal to any of the shiny gold trinkets I have seen in other museums.

More on my US trip next week – and there’ll be more history involved and a bear hunt in the Great Smoky National Park.